Geikomi Resources

Geikomi Terms:

Geikomi (ゲイコミ)

Bara (薔薇)

Nonke (ノンケ)

Common Body Types: gacchiri (ガッチ), gachimuchi (ガチムチ), gachidebu (ガチデブ), debu (デブ)

Breaking Misconceptions of "Bara vs. BL"

Tagame on ‘My Brother’s Husband’

A Brief History of Male-Male Sexuality in Japanese Culture

Sources & Citations for Further Study

Definition of Geikomi (ゲイコミ):

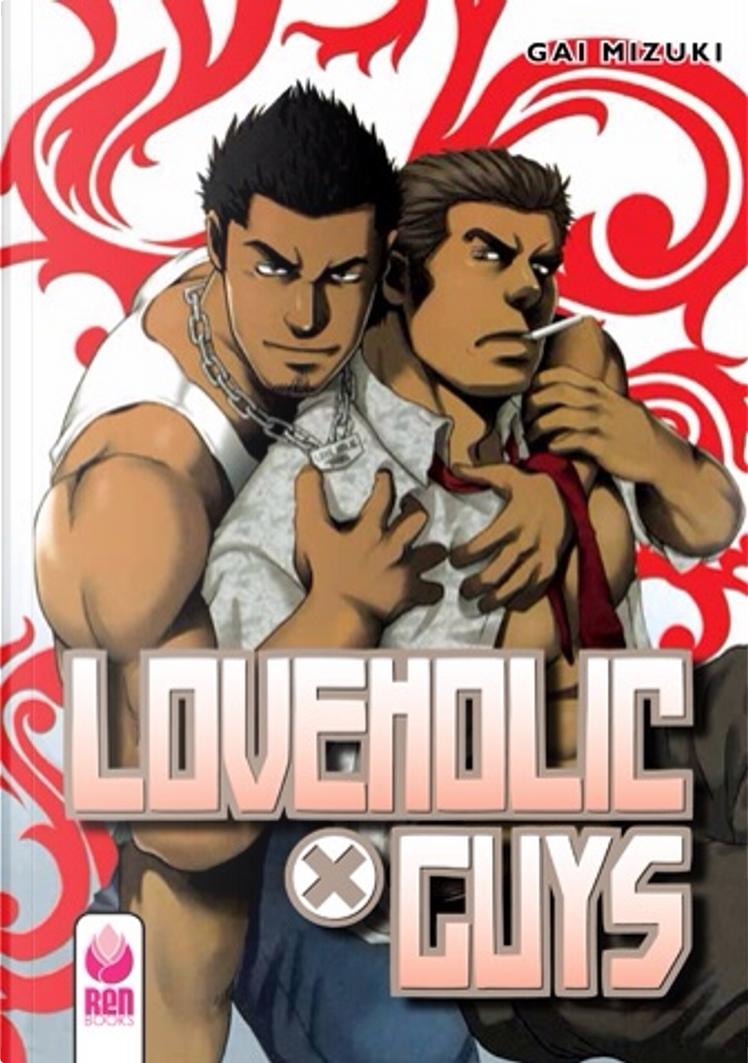

Geikomi or “Gay Comic(s)” refers to the genre of erotic comics published and marketed to adult gay men. Frequently called “gei manga” (ゲイ漫画), it is different from the Boys’ Love genre in that its targeted audience is exclusively adult gay men. Therefore its contents are tailored to suit that audience. (“Geicomi.” https://futekiya.com/what-is-geicomi/.)

Common specific body type categories:

gacchiri - muscular (robust, well built) ( - ガッチリ

gachimuchi - muscle/chub (slang - stocky, beefy) - ガチムチ

gachidebu - muscle/fatty - ガチデブ

debu - fat - デブ

*searching for these in tags (in Japanese) online can help you find geikomi content you're looking for

Definition of Bara (薔薇):

Literally means “rose.” Its common usage can be traced back to the first magazine catering exclusively for gay men in Japan, Barazoku (薔薇族). (“Bara.” https://futekiya.com/what-is-bara/.)

"In 1987 Bara-Komi publishes Junichi Yamakawa's one-shot manga "Kuso Miso Technique" – a matter of little consequence in 1987, yet the comic will rise to worldwide notoriety in 2002, when bootleg scans go viral on... 2channel. Consequently, an influx of interest in gay manga inspires an avalanche of piracy and the overseas misappropriation of the term "bara" as a genre label." – Massive: Gay Erotic Manga and the Men Who Make It (2015)

"The title of Bara-Komi raises an important linguistic sticking point for Tagame: the widespread misuse of the term "bara." Literally "rose," bara is an antiquated slur for gay men. It took on a new layer of meaning in the 1960s as the title of the private circulation gay publication Bara, and the subsequent mass-market magazine Barazoku (Rose Tribe). "It was very shocking and sensational to publish something in the jargon of the hetero nomenclature for gays," says Tagame. "It's exactly like the word 'pansy' in English. Whereas gays probably don't call each other 'pansies,' since it's not necessarily a good thing, to reappropriate it was a big deal. But by the time I was getting bigger as an artist, that word was almost obsolete, and we no longer use it. It was important for us to call ourselves 'gays' and 'homosexual' rather than 'bara,' which is just what hetero people call us. "Gay" became the primary identity label for homosexual men as a more internationalized concept of LGBT identity gained political and social ground in Japan. "By the 1990s," Tagame remembers, bara "was totally obsolete, Barazoku magazine was becoming obsolete, and the whole nomenclature was about to completely expire. But in the early stages of the Internet, when people were on all these Internet boards, basically, the people running these forums were straight, so they called the gay board the 'bara' board. Of course, the Internet is how foreigners discovered our work. They saw that this whole section was called 'bara,' so that's how I believe foreigners started to use and appropriate that word. The word has come back to life, unfortunately, and I have to say personally, I'm sort of against it. I don't call my own work 'bara' and I don't like it being called 'bara' because it's a very negative word that comes with bad connotations." (Massive, 40)

"Barazoku, the “rose tribe,” was used at the time to indicate gay men. Nowadays in Japan, the word “bara” has taken on a negative connotation, expressing effeminacy, similar to the English phrase “nancy boy.” But in America, “bara” (i.e. fans of beefy men) has been adopted by the bear fandom within comics. One cannot in confidence state that “bara” means bear, since in its homeland the word actually means the very opposite. In Japan, erotic comics starring beefy men are referred to simply as “gay comics” (ゲイ コミックス)." Friedman, Erica. By Your Side: The First 100 Years of Yuri Anime and Manga (p. 24). Journey Press. Kindle Edition.

Also see an informative presentation by Thomas Baudinette on "Bara manga and gei komi"!

"Within this presentation, Thomas Baudinette provides an outline to the bara/gei komi genre, discusses its marketing and its consumption by gay men and introduces some popular producers of the genre. Thomas also discusses some of the major controversies surrounding bara/gei komi, particularly investigating its relationship to yaoi/BL." https://www.academia.edu/11719439/Bara_manga_and_gei_komi

More history of 'Bara' here (See year 1987)

Website Author’s Note: 'Bara' at the very least is a largely outdated term and not modernly used as a visual/industry/umbrella term for Gay men's manga. It doesn't necessarily universally refer to a buff visual or body style, it relates to a decades-old reclamation & popular magazine (Barazoku) that went out of style by the late 90s. While it's fine for JPN men to use it, outsiders calling all 'buff' characters 'Roses' isn't accurate, it's outdated. In terms of industry and umbrella terms, it's just 'Gay Comics' = Gei Komi. 'Bara' becoming a staple of Western vocabulary was likely due to homophobic men on 2Channel causing certain comics to go viral. Since the early 2000s Anglophones aren't bothering to update their language regarding it. Many gay Japanese men have compared the usage of 'Bara' similar to saying or calling a gay man a 'Pansy' in English. Since using Pansy as an insult is less recent in English, I think a potential modern comparison could also be 'fairy'. People have reclaimed it, some people happily use it! Some identify with it, others don't, but Gay men's media as an overall collective isn't referred to, categorized, or sold as 'Fairy' media or 'Fairy style' etc.

Definition of Nonke (ノンケ):

"As with a lot of jargon coming from the gay community in Japan, nonke was already used in the first gay magazine publication, Barazoku, during the mid-1970s. The word was commonly used among gay and lesbians to describe heterosexual people from their perspective. However, within the gay community, when a nonke person sleeps with the same sex and afterward discovers their sexuality, then the person is not a nonke, but merely a person who didn’t realize that they’re actually gay." (“What is Nonke?” https://web.archive.org/web/20230315231542/https://futekiya.com/what-is-nonke/)

Can also be ascribed to a type of Gay pornography category in which queer men seek out straight male characters or performers as desirable. (See more in: Regimes of Desire (Chapter: Japanese Gay Pornography, sub-section: 'Fetishiszing the Straight Man', Baudinette 2021)

Common Misconceptions about 'Bara' & Geikomi

Website Author’s Note: Please be aware that these quotes are from around 2014-2017. As time has passed there has been less and less division between BL & Gei Komi categories. How individuals categorize their own personal work is not set in stone and can vary considerably. While you may outwardly view a piece as Gei Komi the creator may think of their work as BL. Looking at a work you assume may be a BL could be categorized as 'Gay (Gei) Manga'. This is why it can be reductive to attempt to segregate narratives and visual styles as exclusively made for or by either Men or Women. Also, Just because a gay man created something does not mean he necessarily made it with the intent of being "good" representation or necessarily realistic. It also doesn't mean that he is representing all gay men equally.

People of any gender or sexuality may publish in both demographic categories:

GENGOROH TAGAME stated in 2015:

"When I look at gay art in comics as a critic, I get really anxious about that division precisely because the simplistic way of dividing it is that BL represents more romance, narratives, thinner body types, more effeminate characters. And then so-called “gay manga” would be just more diesel, big guys and more hardcore sex, etc. But what happens when the creator is a woman doing more hardcore work? Is that considered gay? Is it BL just because she’s female? Is it about the audience, or is it about the creators? So those are definitely things I think about a lot as a critic. Furthermore, going back to the gender of creators, that’s problematic as well because sometimes BL creators– and I’m speaking just from personal acquaintance with some of these creators– may be biologically female or identify on the page as heterosexual women, but sometimes they’re actually lesbian or transgender. And then sometimes it’s the case that a woman will draw sort of muscle-y characters and then take on male pen names for publication in gay media. Which is also very… not problematic, but just raises questions, just how do we start to categorize? There are anecdotes from the editors of gay magazines who see these submissions, see a male pen name and assume that they’re men, write to (the artist), want to meet, when they meet, it’s a shock! (laughs). (TCAF, 2015)

Yarou Festival (https://yaroufes.info/), a festival for Gay Comics also doesn't exclude women from participating:

Yarou Festival FAQ: "Is Yaro Festival for men? Is it for women?"

"We do not operate in a form specifically for men or women. Nor is it a specific sexuality event.

In the past, 90% of the participants were men, but there are many women who participate in the circle, and the number of men and women is evenly divided. We hope for your reference."

Many queer men view BL and geikomi as equally valid genres:

"These four men understood BL and geikomi as interconnected. They all variously argued that both BL and geikomi represent equally valid yet fantastic depictions of "gay identity" (gei aidentiti). For this reason, the four men saw no need to sharply disassociate BL from geikomi when discussing their consumption of gay media. Yoichi, whose consumption of both BL and geikomi is highly casual, explained that to conceptually separate the two genres made little sense; he stated, "They are both manga, two sides of the same coin... They have gay guys in them, even if they look different... so they're gay manga." This admission was despite the fact that Yoichi was a firm believer in the primacy of hardness and despite his denigration of soft masculinity." (Baudinette)

Geikomi is generally associated with being more sexually explicit while BL is mostly associated with romance:

Many anti-BL and anti-fujoshi critics share the opinion that only cisgender gay men should be writing about gay male characters. The problem with this is that the gay male experience is not universal. Gei Komi or "Bara" (The outdated term still used by Anglo fans) comics made "by gay men for gay men" largely focus on a hyper-masculine perspective and contain more overt sexual elements. Fumi Miyabi, a Gei Komi mangaka even states, “the manga has to be erotic, and it can’t not include sexuality… they’re just not meant for more vanilla content” (Massive - 189). Gay men who want more romantic content have to find it via BL manga

"Throughout interviews, [the men] argued that the depictions of masculinity in geikomi were "extreme" (kageki) and further understood this extremeness as highly desirable. This was an opinion shared by other young gay men I met during fieldwork: they viewed geikomi positively (even if they did not necessarily consume it) because it conformed to their preconceived notion that desirable gay masculinity is both "hard" and "violent," (Baudinette).

"For many of the men with whom I spoke, Japanese masculinity was becoming soft; they saw an increasing focus away from hard masculinity since such gendered performances were supposedly no longer popular among young women. That is... viewed as a curse that was somehow weakening or diluting contemporary Japanese masculinity. Most of my interlocutors viewed the bishōnen's rise in Japan negatively and positioned Ni-chōme as an important space of resistance where hard masculinity remained prominent and respected." (Regimes of Desire - Baudinette)

“In the yaoi ronsō women who depicted and looked at men having sex with men were criticised for discriminating against gay men. However, compared to gay manga drawn by gay men for gay men, BL manga cannot be said to be more abusive. In both gay and BL manga, the men depicted are not necessarily gay as in having a gay identity. Thus, the reason why BL manga were criticised by a gay man cannot only lie in their depictions of gay men since, in that case, gay manga should equally have been the focus of critique. Satō feels uneasy about women watching what he regards as depictions of gay men—he wants such depictions to have limited access. He wants depictions of homosexuality to remain in a closet, viewed only by an inner circle of gay men. However, limiting the audience to those who regard themselves as gay men inevitably limits the opportunities for young and possibly isolated gay men to find gay characters with whom to identify, which is a reason why it can be seen as fortunate that BL manga are popular and easily available.” (Lunsing)

"Yaoi/BL, being produced by women for women, is more likely to reflect an understanding of gay intimacy premised on an ethics of care when compared to the models of gay intimacy emerging from within mainstream gay male culture.[40] This suggests that yaoi/BL is the sort of subjugated knowledge that may have something valuable to contribute to the re-envisioning of gay intimacy, especially if coupled with the point, made above, that yaoi/BL was born as a reaction to the formulaic constraints of marital heteronormativity. To paraphrase Halberstam (2005), yaoi/BL “culture constitutes…a counterpublic space where white [heteronormative and metronormative gay] masculinities can be contested, and where minority [gay] masculinities can be produced, validated, fleshed out, and celebrated” (Zanghellini, p. 128).

"These conventions of the yaoi/BL genre are as removed from those of standard Western gay male pornography/sex as they could be. Indeed, I would argue that ‘activity/passivity,’ rather than ‘dominance/submission,’ provides the most accurate conceptual framework for understanding much (if not all) yaoi/BL work. This does not necessarily contradict the observation that producers and consumers of the genre ultimately assert “the right to imagine sex which is not politically correct: that is sex which derives its interest from imagining power differentials, not equality” (McLelland, 2005, p. 74). The reason is clear: power asymmetries do not necessarily have to lead to relationships of dominance and submission." (Zanghellini)

Tagame on ‘My Brother's Husband'

Website Author’s Note: Despite being hailed by many LGBTQ+ Western and Anglophone readers as "Good Gay Representation unlike BL or Yaoi made for Straight Women", 'My Brother's Husband' by Gengoroh Tagame was written to cater to a Straight Male audience's sensibilities. To clarify this does not reduce it's quality, but instead points out the hypocrisy expressed by Western/Anglophone readers: i.e., My Brother's Husband is "good gay representation" despite centering a straight male character battling internal prejudice and homophobia, while BL as a whole is inherently bad because it was made by or for a female audience.

(2014) "Tagame Gengoroh’s “Painting the essence of gay erotic art” Part 1 / Part 2 and (2018) "Influential Manga Artist Gengoroh Tagame on Upending Traditional Japanese Culture" Link:

"I like to think of ['My Brother's Husband'] as Japan’s first ever “gay manga for straight men,” even at the best of times the hurdles I needed to overcome as a gay artist creating a gay manga within a magazine that is mainly read by straight men were quite high. For example, to ensure that I didn’t cause any negative reactions amongst the [straight male] readers of the magazine, I had to pay particular attention to the plot. Therefore, if I employed the kinds of narratives that gay readers and those who enjoy BL would expect, perhaps the story wouldn’t move forward smoothly [for straight male readers]." (Source)

"However, since the time when the word “Boys Love” started to be used — and just as shōjo manga itself started to evolve and grow — it seems to me, looking back from my distanced position, that the discriminatory atmosphere of the past has begun to disappear as the love between two men is beginning to be written more sympathetically [by contemporary BL authors]."

"Supporters of the former yaoi culture seemed to possess a guilty conscious, thinking to themselves “why is that whilst I am a woman, I like yaoi?” They always seemed to have prepared desperate excuses for their preferences, such as “it’s beautiful, so it’s okay” or “it’s forbidden, so it’s okay.” However, as times have changed, the number of people who say “I like BL and there’s nothing wrong with that” has greatly increased. Personally, I think it’s fine if we think of “liking BL (BL-zuki)” as just another form of sexuality."

"By the way, “self-reception (jiko jūyō)” is one of the big themes to be found within my work, basically speaking, I write happy endings for those characters who have accepted their personal sexuality and bad endings for those characters who don’t (he laughs). The more the number of people who perceive their sexuality to be “liking BL” increases, the more open BL culture will become and that can only be a positive development to my mind.""

A Brief History of Male-Male Sexuality in Japanese Culture

(from 'Massive' 2015)

(most up-to-date list https://www.fujoshi.info/database)

Includes pieces that specifically reference and/or discuss gay Asian men's history, media, culture, and preferences.

BOOKS

Angles, Jeffrey. 2011. Writing the love of boys: origins of Bishōnen culture in modernist Japanese literature. Minneapolis: Univ. of Minnesota Press.

Baudinette, T. (2021). Regimes of desire: Young gay men, media, and masculinity in Tokyo.

Ishii, Anne, Chip Kidd, and Graham Kolbeins. 2014. Massive: gay erotic manga and the men who make it.

Leupp, Gary P. 1995. Male colors: the construction of homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan. (1603-1868). Berkeley: University of California Press.

McLelland, Mark James. (2000). Male homosexuality in modern Japan : cultural myths and social realities. University of Hong Kong (Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong.

McLelland, Mark J., Katsuhiko Suganuma, and James Welker. 2007. Queer voices from Japan: first person narratives from Japan's sexual minorities. Lanham: Lexington Books.

McLelland, Mark, Kazumi Nagaike, Katsuhiko Suganuma, and James Welker, eds. 2015. Boys Love Manga and Beyond: History, Culture, and Community in Japan. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

McLelland, Mark J. 2006. Genders, transgenders, and sexualities in Japan. London: Routledge.

AVAILABLE ONLINE

*(Need Help Accessing Articles? Google 'Sci-Hub'!)

A Japanese SOGI. (2022). "A Rose by Another Name is a Pejorative".

Aoki, Deb. 2015. “TCAF 2015 – Gengoroh Tagame Talks Gay Manga, “Bara,” BL and Scanlation.” Manga Comics Manga. July 22,2015.

Baudinette, Thomas (2014) [Translation] Tagame Gengoroh’s “Painting the essence of gay erotic art” Part 1

Baudinette, Thomas (2014) [Translation] Tagame Gengoroh’s “Painting the essence of gay erotic art” Part 2

Baudinette, Thomas (2015) "Bara Manga and Gei komi." https://www.academia.edu/11719439/Bara_manga_and_gei_komi.

Baudinette, Thomas (2017) "Constructing identities on a Japanese gay dating site". Journal of Language and Sexuality

Baudinette, Thomas. (2017) "Japanese gay men’s attitudes towards ‘gay manga’ and the problem of genre". East Asian Journal of Popular Culture. 3 (1): 59-72.

Baudinette, Thomas (2018) “‘Finding the Law’ through Creating and Consuming Gay Manga in Japan: From Heteronormativity to Queer Activism.” Law and Justice in Japanese Popular Culture: From Crime Fighting Robots to Duelling Pocket Monsters: 155–167. Print.

Baudinette, Thomas. (2020). "Japanese Gay Men's Experiences of Gender: Negotiating the Hetero System". Routledge Companion to Gender and Japanese Culture.

Baudinette, Thomas. “Aspirations for ‘Japanese Gay Masculinity’: Comparing Chinese and Japanese Men’s Consumption of Porn Star Koh Masaki.” Porn Studies 7.3 (2020): 258–268.

BL Fan Project. https://blfanproject.com/.

Harada, Akemi. 2016. “Do Japanese Gay Men Read Boy’s Love Comics, Dislike ‘Fujyoshi’?” Nijiiro News, May 3, 2016.

Harada, Akemi. 2016. “Evolved Boy’s Love: How Fujyoshi Could Eliminate Prejudice” Nijiiro News, May 4, 2016.

Hompig. 2015. “The Origin of the “Gays Are Anti-BL” Movement: 2Chan’s “Women-Bashing” on the Online Discussion Board Douseiai Salon.” Hatena Blog. April 4, 2015.

https://web.archive.org/web/20150406014130/hompig.hatenablog.com/entry/2015/04/06/100835. (ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY BETSY LINEHAN-SKILLINGS: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1mrm-ryWlXh1hlBJIFY1ewLfRxwgiuKclMBONQB___3k/edit?usp=sharing)

Hori, Akiko. 2013. "On the Response (Or Lack Thereof) of Japanese Fans to Criticism that Yaoi Is Antigay Discrimination." In "Transnational Boys' Love Fan Studies," edited by Kazumi Nagaike and Katsuhiko Suganuma, special issue, Transformative Works and Cultures, no. 12. https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2013.0463.

Ishii, Anne (2018) Influential Manga Artist Gengoroh Tagame on Upending Traditional Japanese Culture

Lunsing, Wim. 2006. “Yaoi Ronsō: Discussing Depictions of Male Homosexuality in Japanese Girls' Comics, Gay Comics and Gay Pornography.” Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context. Issue 12 January 2006.

Matsumoto, Masaki C. 2018. “A gay man's opinion about yaoi/BL,” YouTube video. 37:53. February 18, 2018. https://youtu.be/VTKla_21ARU.

Matsumoto, Masaki C. 2021 "LGBTQ+ Representation in Japanese Media (Q&A)"

Matsumoto, Masaki C. 2022 "Being queer in Japan (Q&A)"

Mackintosh, Jonathan D. 2006. “Itō Bungaku and the Solidarity of the Rose Tribes [Barazoku]:

Stirrings of Homo Solidarity in Early 1970s Japan” Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context. Issue 12 January 2006.McLelland, Mark. 2004. “From the stage to the clinic: changing transgender identities in post-war Japan.” Japan Forum; Vol. 16, no. 1, 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/0955580032000189302.

Nagaike K. (2019) Fudanshi (“Rotten Boys”) in Asia: A Cross-Cultural Analysis of Male Readings of BL and Concepts of Masculinity. In: Ogi F., Suter R., Nagaike K., Lent J. (eds) Women’s Manga in Asia and Beyond. Palgrave Studies in Comics and Graphic Novels. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97229-9_5

Rotten Boys Club. https://rottenboysclub.dreamwidth.org/.

Yukari, Fujimoto. "The Evolution of “Boys’ Love” Culture: Can BL Spark Social Change?" Nippon.com. September 24, 2020.

Zanghellini, Aleardo. 2012. "Gay Intimacy, Yaoi and the Ethics of Care". Queer and Subjugated Knowledge. Pp. 192-221 (30). DOI: 10.2174/978160805339111204010192.

Zsila Á, Pagliassotti D, Urbán R, Orosz G, Király O, et al. 2018. Loving the love of boys: Motives for consuming yaoi media. PLOS ONE 13(6): e0198895. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0198895.